Death from heart disease: the socioeconomic disadvantage

Cardiovascular disease claims the most lives of any illness. Ahead of World Heart Day on September 29, we offer insights to debunk popular assumptions that affect advances in knowledge and improvements in health.

In 2016, 17.8 million people died from cardiovascular disease (CVD), a group of conditions that includes coronary heart disease and major events such as heart attack and stroke. This figure represents 31% of all deaths globally and, three years on, CVD remains the biggest killer of people worldwide.

Many assumptions exist about who is most affected by CVD. One common misconception is that heart disease is one of affluence, i.e. that it is more common in high-income countries with developed economies than low-income countries. In some ways this view seems to make sense; CVD development is in part influenced by lifestyle practices such as smoking, obesity and being physically inactive; factors more often associated with people in higher income countries than nations affected by widespread poverty and food insecurity.

In fact, the truth is that the burden of CVD is increasingly weighted towards low-income countries.

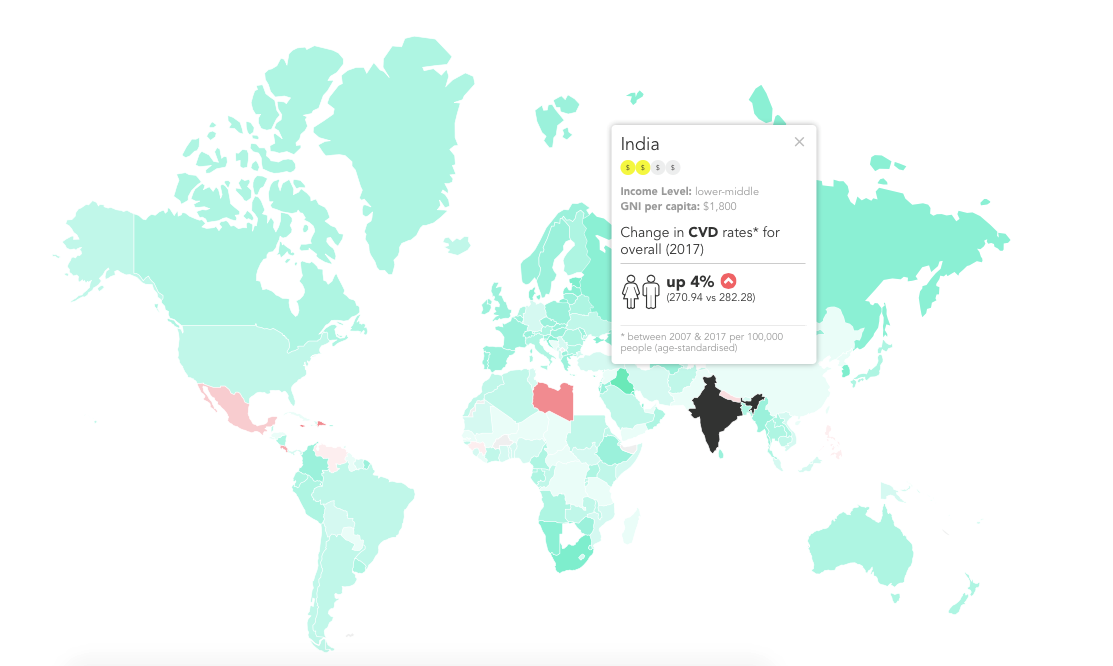

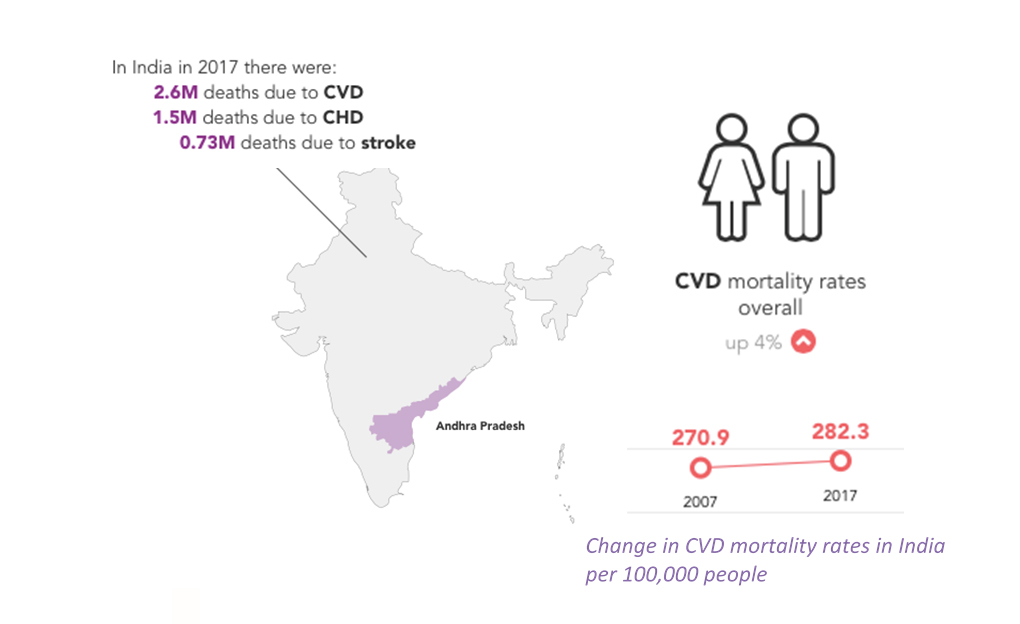

While overall mortality rates from CVD have decreased globally over the past 12 years, in some countries – almost all of them low- and middle-income – the rates have actually increased. As our interactive data visualisations reveal, between 2007 and 2017, overall rates of CVD increased by 4% in Georgia and India, by 5% in Nepal, and by 2% in the Philippines, while rates decreased by 12% and 22% in the United States and UK respectively over the same period.

[Change in CVD mortality rates in India between 2007 and 2017]

The data highlights the startling truth that where you live impacts significantly on whether you live. Over three-quarters of deaths from heart disease occur in low- and middle-income countries. Elsewhere, the downward trend in CVD rates and proportionally minor share of mortality suggests that prevention and intervention around CVD is either more widely available, accessible, affordable or effective in the most affluent nations.

This is compounded by the fact that, within countries, especially those considered affluent, the most socioeconomically deprived are disproportionality affected by the life adjustments associated with heart disease.

Another assumption is that CVD is a disease that mostly affects men. In absolute terms, this may be the case, but evidence shows that women with CVD are relatively more likely to be affected by disease-related disability and death. Our visualisations describe how, just two years ago, mortality rates from CVD were 2.6 times higher in low-income countries than high-incomes countries for women, and 1.9 times higher for men. The reality is this: those most likely to die from CVD are the poorest women in low-income countries, most likely based in remote communities.

Indeed chronic diseases such as CVD are closely linked with poverty. As rates of these kinds of diseases escalate globally, poverty reduction initiatives in low-income countries will be feel the strain due to the lengthy and expensive treatment required, which together with other associated healthcare costs, can quickly have catastrophic effects on a family’s financial situation.

World Heart Day isn’t just about awareness-raising and myth-busting, but also a time to consolidate initiatives aimed at reaching those most vulnerable to CVD and its associated tragic impact on quality of life and financial security.

One solution The George Institute for Global Health has developed is our Systematic Medical Appraisal, Referral and Treatment (SMART) digital health platform.

SMARThealth is a mobile-based clinical decision support system for primary health care workers which has had demonstrated impact on the health of thousands of people across six countries already. It enables health workers of all skill levels to provide high-quality, affordable and sustainable preventive care to patients at high-risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease and stroke.

SMARThealth has been successfully trialled in countries such as India and Indonesia, where deaths from CVD are on the rise, and where the most remote rural communities often experience patchy or inadequate healthcare but have strong mobile network coverage. Community health workers are using this technology to deliver essential healthcare to those who previously had little or no access, potentially saving thousands of lives.

In India, even a 1% reduction in the number of deaths due to coronary heart disease and stroke would save a staggering 22,700 lives each year.

So around World Heart Day on 29 September, please share our new data visualizations that use evidence to challenge inequities in heart health, and join the call for action towards universal health coverage, ensuring that everyone has access to quality and affordable care, whenever and wherever they need it.